|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

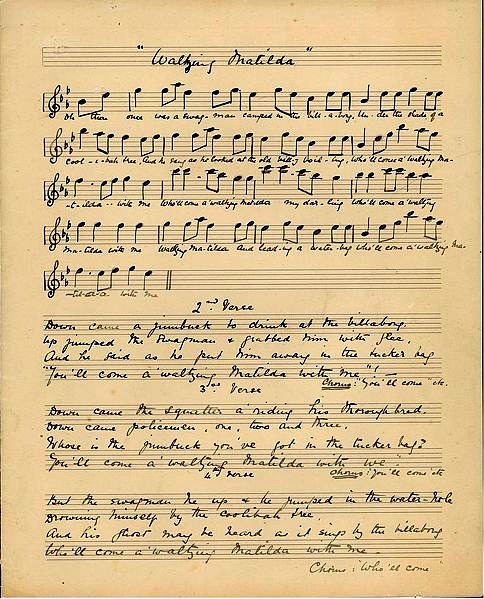

the score of waltzing matilda

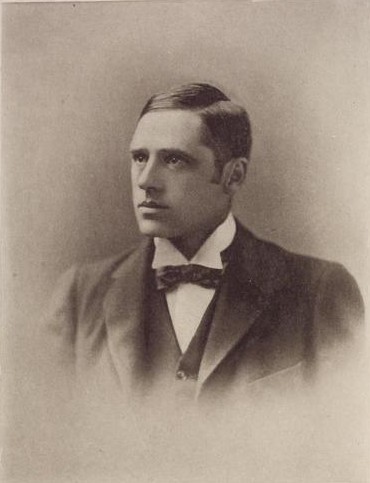

Most people credit Banjo Peterson with composing Waltzing Matilda, which has proved to be a very popular song and a great success all over the world. Although there is little doubt that Peterson write the original lyrics, as we shall see, the identity of the originator of the melody is obscure. As with other successful music, it has inspired many variations, most of which are based on Banjo Peterson's lyrics; other versions of the song based on the melody have alternative lyrics with very different objectives and stories to tell. Below is a copy of the composer's entire original score, just as he set it down with pencil and paper; it's an almost-life-sized reproduction designed to make it legible and easy to read. It contains all four of the song's verses and its refrain. Click the score at any time to hear the song again. At the left, Christina Macpherson, credited with hearing the melody to Waltzing Matilda and recognizing its full potential. At the right, Andrew Barton Paterson, known as Banjo Paterson, a popular nationalist Australian poet of the time and the person who wrote the lyrics.

historyHere's the story of how the song was born. Read it as you listen. Christina Macpherson was the daughter of an Australian squatter, a relationship that put her in an excellent position to appreciate the subject matter and the sentiments expressed by the lyrics of the song as we know today. However, at the time she first heard it, the lyrics we know today did not exist and the song was nothing like the song that eventuated. Details of how the song came to be are murky. One theory is that Waltzing Matilda started life as a Scots folk tune which was transformed into a popular Scots song called Thou Bonnie Wood of Craigielee. Barr composed the music in 1818 and Tannahill wrote the words in 1805; the tune was transcribed for brass band by Thomas Bulch in 1893. At this point, Waltzing Matilda had yet to be born. When Christina heard Thou Bonnie Wood of Craigielee at a public event she was instantly enthralled by its melody. Not a professional musician herself, she did her best to commit the tune to memory and to transcribe it so as to preserve it for conversion into something else. In one version of the story, Christina's brother Bob, an acquaintance of Peterson, is thought to have told him about an Australian sheep sheerer who, being pursued by authorities after participating in a violent 1894 Queensland sheep herder's strike, shot himself at an outback waterhole rather than allow himself to be captured. This event inspired Paterson to write Waltzing Matilda and use it as a socialist anthem in 1895, one year after the strike. In another version of the story, Paterson penned the song to please Ms. Macpherson, with whom he was enamored.

the score—words & music togetherTo gain insight into what a score is for and what it is like, The Muse Of Music suggests that you start by playing the song again. To do this, click the picture of Banjo's score, below. This time, follow along by reading the score as the song plays. Read Banjo's lyrics as Slim and his Bushlanders sing. The Muse realizes that Banjo's handwriting is not the best, and that the image of his score is blurred. So, The Muse has provided a printed an extra-large copy of Banjo's lyrics to help you decipher what you read in case you run into trouble (see below, under the score). Although Banjo's original version and Slim's version are similar, don't expect Slim's version to exactly match the original one. Slight variations among Waltzing Matilda renditions are common. In popular or classical music, variations are common. Variations are permitted—even relished—as a consequence of musical creativity and artistic freedom; that's one of the wonderful aspects of art.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lyrics | Translation |

|

|

about banjo's scoreNotice that Banjo has used paper on which staves have been preprinted. In his own hand, he has added or omitted these items:

Banjo did not put a marker on the page to show readers where the refrain begins because he expects a reader to figure that out for himself. Here's how:

Why ask a reader to look for a refrain instead of marking it on a score? This method for indicting a refrain is an economical shorthand that saves composers the trouble of writing a refrain over and over after every verse. It saves paper, too, and cleans up the score so that it's less messy. |

|

—tip— take it easy Rome wasn't built in a day, as the saying goes. As you read about the score of Waltzing Matilda, you may encounter some musical facts you don't have the background or musical training to understand. If that turns out to be the case, don't let that discourage you. The Muse hopes you'll stick to your guns and keep trying; you'll probably walk away understanding more than you realize and you'll lay a foundation for future progress. |

conclusion

Now that you've got the words alined with the music, try playing the song again. This time, follow the score while you sing the lyrics along with Slim Dusty and his boys and girls. Sing the lyrics to yourself if you're shy about your voice.

Notice how the song springs to life when you know the story behind it, understand the words, and think about the story they are telling while you are hearing the melody. The Waltzing Matilda melody is great by itself but the words, melody, and meaning together are much more powerful. Reading a score while listening to music is a way to facilitate this integration process.

By now you can see why there's a lot to gain by following along—by reading a score while you listen to the music.

Banjo Peterson's score for Waltzing Matilda illustrates many of the characteristics shared by scores everywhere. Now that you've explored Peterson's work, you're ready to move on to other scores.

eTAF recommends

[Add books about scores and score web sites.]

Convert this page.

|

|

Search this web site with Electricka's Search Tool:

tap or click here

Electricka's Theme Products

Shop At Cafe Press

This web site and

its contents are copyrighted by

Decision Consulting Incorporated (DCI).

All rights reserved.

Contact Us

Print This Page

Add

This Page To Your Favorites (type <Ctrl> D)

You may reproduce this page for your personal

use or for non-commercial distribution. All copies must include this

copyright statement.

—Additional

copyright and trademark notices—

The

song you are now hearing is Waltzing Matilda, called by some the second or

unofficial national anthem of Australia. The version you're hearing is

performed by

Slim Dusty, a singer of Australian songs and himself a tradition in

Australia. In this

rendition, Slim is accompanied by his Bushlanders.

The

song you are now hearing is Waltzing Matilda, called by some the second or

unofficial national anthem of Australia. The version you're hearing is

performed by

Slim Dusty, a singer of Australian songs and himself a tradition in

Australia. In this

rendition, Slim is accompanied by his Bushlanders.