welcome to

western Music notation

Welcome to these pages, where The Muse Of Music explores the subject of

notation in Western music.

about Western Music and its notation

In a musical context, Western refers to and designates the western

part of the world, as distinguished from the East or Orient. Another name

for this part of the world is the Occident.

Western music designates the music produced by countries,

cultures, performers, and composers with aesthetic roots in the Occident.

Western music notation refers to the archetypical notation

system used by

composers or performers when they compose, write, or play Western music.

Western music's notation system is one of the most important factors that distinguishes

modern Western music from

other kinds of music. This notation system makes it

possible for composers to write music in such a way that it can be universally

communicated and recorded throughout the West, and indeed throughout the

world. It makes it possible for performers trained in reading Western

notation to play Western music.

- For an explanation of musical notation and musical notion systems, see

The Muse Of Music's page called Welcome To Music Notation:

click here.

Western music is the music of Western

civilization, the civilization that evolved in and from cultures of Greek,

Roman, and European origin. In

classical music, Western music comprehends the music and musical traditions

of Medieval times, the Renaissance, the Baroque period, the Classical

period, the Romantic period, and 20th century classical music in Europe,

America, England, Russia, and neighboring nations. In popular music, it comprehends

Acid, Bluegrass, Blues, Country, Disco, Folk, Hymn, Jazz, Metal, Neofolk,

Punk Rock, Rap, Rock & Roll, Soul, Spirituals, Swing, and more. These

musical fields make up the primary types of music in Western culture today, but no

doubt other forms exist and new ones will be developed as time goes on.

Western Modern notation (or simply modern notation) is a specific and particularly important

collection of closely related notation

systems that dominates Western music composition and performance today. Modern Western notation was originated

by and for European classical music, but it is so successful it is now used by musicians

who play music typical of many other genres and styles throughout the world,

including some Oriental ones, as well

as by the vast majority of classical and popular musicians of the Western tradition.

All of these specific Western musical traditions have one thing in

common: they adhere to and employ a similar basic musical notation system and a similar

collection of musical composition methods, standards, performance practices, and

musical instruments.

Western notation is here to stay

There's no getting around the fact that Western notation is here to stay.

It's entrenched because: 1) it's the de facto standard technique for

creating and writing

Western music, 2) Western music is intrinsic to world culture, and 3)

Western notation is a brilliantly designed technical system for playing,

composing, and recording musical sounds, as well as a theory for explaining

how and why music as the effects on listeners that it does.

The technical design of Western music has evolved over thousands of years

as a result of an ongoing random and piecemeal analysis of the physics,

mathematics, and neural character of sound, as well as from systematic

studies and pragmatic experimentation conducted by thousands of folk and

professional musicians, scientists, mathematicians, religionists, and

philosophers.

The development of Western musical theory reaches as far back as the

research of Pythagoras, the sixth century BCE Greek philosopher,

mathematician, and musician, whom many scholars credit with founding the

science of music. He's the same Pythagoras who's credited with devising the

famous geometric theorem you probably studied in high school, the one that

states that in a right-angled triangle the area of the square of the

hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of other two sides the squares

of the other two sides.

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered that musical notes could be

translated into mathematical equations when one day he passed blacksmiths at

work, and the thought occurred to him that the sounds emanating from their

anvils were beautiful and harmonious. He decided on the spot that whatever

scientific law caused this to happen must be mathematical and could be

applied to music and began a serious investigation of the properties of

sounds.

Later he discovered that the ratios between successive notes hear by the

ear are relevant to such factors as string length, and that a note sounded

by a plucked string that is higher in pitch than its predecessor is

harmonious only if its length is half that of the first; also, he discovered

that the next note above the first one is harmonious only if it is produced

by a string that is 2/3 its length, and so on.

In part because of musical and other non-musical effects like these,

Pythagoras created a theory of numbers. He believed that the planets and

stars moved according to mathematical equations, which correspond to musical

notes; hence they produce a symphony. Subsequently, Plato adopted

Pythagoras' ideas and described astronomy and music as twinned studies of

sensual recognition: astronomy for the eyes, music for the ears, and both

requiring knowledge of numerical proportions.

Notions like these stimulated intense investigation into the underlying

physical and mathematical nature of music among Pythagoras' students and in

the Western world at large. They led to the ancient metaphysical concept of

the harmony or music of the spheres that became popular and influential in

the Middle ages and which continued to stimulate intense investigation for

centuries afterward.

In large measure, as a result of these in-depth Western World aesthetic

and scientific investigations into the nature of sound, its relation to

music, and its affect on the human psyche, Western music has evolved into

one of the world's most powerful, sophisticated, pristine, subtle,

self-consistent, well structured, and technically complex composition and

performance tools available to musicians; and so has the music that creative

Western musicians have succeeded in producing. Western music is so

sophisticated and complex in so many subtle ways that The Muse Of Music must

decline to explain in detail here the nature of Western music technology and

the specific reasons for its possession of these attributes.

Unfortunately, despite the inherent superiority of Western music

technology, the physical and cultural isolation of the West tended to

suppress the Eastward expansion of these innovative musical ideas and

inventions to other parts of the world until relatively recent times.

Why and how did Western musical theory, notation, composition methods, performance practices, and

instruments initially catch on in the West? Why do they remain standards

there? Why did this superior musical technology eventually spread to the East?

Largely because of

the diminishment of cultural barriers and improvements in communication

technology.

For good reasons, indigenous systems for playing and writing music

continue to appeal to many musicians and audiences in regions, countries,

and cultures around the world. However, the Western musical tradition offers

benefits that have caused Western music to be adopted by most musicians in

most cultures everywhere:

- The Western notation system is flexible; it adapts readily to

preexisting traditional ways of playing that encourage its rapid acceptance

and adoption.

- Western music allows for the

invention and expression of new kinds of music and new composition and performance techniques.

- Many musicians who compose or play Western music are born and raised in the Western world.

- Many Westerners are immigrants from other nations, or they're children

of immigrants. They become enculturated in Western traditions from the time of birth,

or they move with their parents to a Western nation at an early age and are raised in its ways.

Later in life, a portion of them become musicians and eventually return to

their homelands or to other parts of the world, where they perform Western

music and teach others about what they've learned.

- Some musicians who are native to the Orient are influenced by Western musical traditions

in situ;

they become acculturated to Western music by a variety of different kinds

of Western influences that act on them in their native surroundings.

The enculturation process is straightforward and easy to understand:

people brought up in a culture absorb it from their surroundings in their

formative years; they soak it up starting from birth as a blotter soaks up excess ink.

But acculturation is a more complex and subtle process. Here are two

living examples of how and why it has worked:

Zubin Mehta

As an example of acculturation, consider Zubin Mehta, the famous

conductor of Western music and Western orchestras. He was born into a Parsi

family in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, the son of a father who was a

violinist and founding conductor of the Bombay Symphony Orchestra. He

attended a Catholic high school and college in Mumbai and became a music

student in Vienna at the age of 18. Also at the same Vienna school with Zubin Mehta were conductor Claudio Abbado, an Italian, and Argentinian-born

conductor–pianist Daniel Barenboim, who holds citizenship in Argentina,

Israel, and Spain.

- At right, above, Zubin Mehta is pictured in casual dress during a practice session

with an orchestra.

yo-yo ma

Yo-Yo Ma, the famous cellist of Chinese extraction, provides us with

another example of acculturation.

His father, Hiao-Tsiun Ma, was born in China and studied Chinese music

there. In 1936 he escaped the Japanese war by moving to Paris, where he

studied Western music at the Sorbonne. During the German occupation of

Paris, he memorized Bach in daylight hours and at night played the Bach he

had memorized for solace during blackouts.

Yo-Yo's father received a doctor's degree in musicology, with Chinese

music as a specialty, and performed professionally as a violinist.

Yo-Yo was born in Paris in 1955 and his family moved to New York in 1961

when he was five years old. He was raised in a musical family (his mother

was a singer) and showed musical promise very early by taking up the cello

at the age of four. His father, being schooled in Western music, and Yo-Yo,

being raised by musical parents in a New York household, is it any wonder

that the youngster absorbed Western music?

- At the right, Yo-Yo Ma with his cello.

Today, when Yo-Yo isn't playing music in the Western tradition, he

honors his father's memory and demonstrates his influence by playing

Chinese and Oriental music in addition to Western varieties.

The Muse Of Music has chosen to embellish the Muse's welcome page on

music with a piece called Blue

Little Flower, a Chinese traditional song from an album called Silk

Road Journeys: When Strangers Meet, in which Yo-Yo Ma plays the cello.

Ma has been instrumental in forming the Silk Road group of musicians and in

playing with them, displaying his versatility and demonstrating that

there's no need to give up other musical traditions in order to acculturate

to Western ones.

- Hear a selection from Blue

Little Flower by visiting the page called The Muse Of Music Welcomes

You: click here.

It's not difficult to appreciate Mehta's acculturation into Western music

once the in-home influences of his younger years are taken into account; nor

is it difficult to see why Ma trained and developed in the Western

tradition. But what about musicians who were not brought up in

Western-looking households yet who have adopted Western music? How do they

come under its spell?

Starting in the mid-20th century and continuing today, worldwide

communications have improved to the point that Western music reaches ears

around the world. Other musicians not brought up Western musical traditions,

who in earlier times would not have been exposed to Western music, are now

hearing and embracing it because they find in it so much that is good,

because it expresses fresh and unfamiliar sounds, new ideas, and new points

of view, or because it offers opportunities for them to reach very large

audiences. theyfind Western music to be a vehicle for expressing sounds and

ideas they cannot otherwise express.

History

Western music and Western notation began with plainchant, the first music

and musical notation system of Europe. Plainchant is the music that was sung by monks of the

Roman Catholic Church starting in the 8th century CE. It is still sung in

monasteries today, although less often than in the Middle Ages; and Catholic

priests sing in a style similar to plainchant when they celebrate High Mass.

Plainchant is used to accompany the text of the mass and the canonical

hours, or divine office. A select few secular choirs who view plainchant from a musical, not a

religious, perspective, specialize in ancient music; they sing plainchant at

live performances and make recordings that can be purchased.

Plainchant forms the core of the musical repertoire of the Roman Catholic

Church. It consists of about 3,000 melodies collected and organized during

the reigns of several 6th- and 7th-century popes. Plainchant is also known

as Gregorian chant because Pope Gregory I, the Great, pope from 590

to 604, was most instrumental in collecting and codifying these chants.

Plainchant notation did not employ a

staff and used neuma or pneuma, a system of dots and strokes

placed above the text instead of the musical notes with which contemporary

musicians are familiar. The music and the notion

system did not have the ability to express precise pitches or times, but that

was acceptable then because plainchant deliberately diminishes the

importance of changes in pitch or time.

Although neuma or pneuma symbols evolved into the symbols

we use to represent musical notes today—if one squints,

once can can recognize a vague similarity between vertical strokes and

checkmarks or dots and oval shapes—it would be hard for most

contemporary musicians to read plainchant because it is radically different

from modern notation.

At

the right is an image of a plainchant score dating from the 13th century.

Notice the dots and checkmarks and the staff (also called stave) consisting of red lines. The staff was not invented until

the 11th century by Guido d'Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk who lived

from 995–1050. His idea was to combine a staff with the neumes that were

introduced in the 8th century. Guido d'Arezzo's staff had 4 lines. In turn,

the 4-line staff led to development of the 5-line staff in the 14th

century. It is safe to say that without today's five-line staff, there

would be no practical way to write modern music and therefore no composers.

At

the right is an image of a plainchant score dating from the 13th century.

Notice the dots and checkmarks and the staff (also called stave) consisting of red lines. The staff was not invented until

the 11th century by Guido d'Arezzo, an Italian Benedictine monk who lived

from 995–1050. His idea was to combine a staff with the neumes that were

introduced in the 8th century. Guido d'Arezzo's staff had 4 lines. In turn,

the 4-line staff led to development of the 5-line staff in the 14th

century. It is safe to say that without today's five-line staff, there

would be no practical way to write modern music and therefore no composers.

Plainchant is

flat, slow-paced, regular, almost monotonic and

otherworldly music. Yet anyone who has heard it

can attest to the fact that it can express a surprising amount of musical

complexity, despite the difficulties with pitch and time, and other

limitations inherent in its notation system.

The plainchant notation system succeeded because it was

up to the tasks set for it at the time. First, there was no need for a more

more powerful notation system because the music was so simple and lacked

variety. Second, the monks who sang plainchant were schooled in what to

sing before they read the score; they only needed an occasional glance at

the melody and words, one that would remind them of what to sing next.

Originally, most secular music was not written down because composers who

wanted to record their own music were too poor to buy writing materials;

only the Church could afford them. However, as people became affluent and music became more and more secular in character and purpose,

pressure grew to develop a notation system capable of expressing more and more musical

subtlety and variety. More and more music was being played

by musicians before a greater range of audiences in more and more places; a

way was needed to distribute music by other than personal contact. These

capabilities and needs spurred

musicians to innovate musical notation systems that could keep up, and Western

music evolved gradually to meet these challenges.

For example, the stave appeared in the 10th

century; a system of fixed note lengths arose in the 14th century; and

vertical bar lines that divide the staff into sections appeared in the 15th

century. By the early 16th century, notation had assumed much of its modern

form, with the essential components of staff, clef, , time signature, and

durational values, though bar lines only gradually became widespread during

the 16th and 17th centuries as an aid in ensemble performance. Regular measures (bars) became commonplace by the end of the 17th

century.

modern notation systems—overview

As indicated above, today one notation system, called Western notation, dominates Western music.

It takes its name from the fact that it was developed by and for classical

European or Western musicians and for Western audiences. Despite

its name and its history, Western notation is not limited to countries in the

West; it is used in many non-Western countries around the world, as well as in Europe.Yet, despite its popularity, some other

countries find good and proper reasons for continuing to use notation

systems of their own devising, instead of or in addition to Western

notation.

For example, in modern times, raga, the classical music of

northern India, employs a

notation system called sargam, which names seven basic pitches of a

major scale. in Java and Bali, several notation systems were devised

by scholars at the end of the 19th century, initially for archival purposes.

An Indonesian notation system for the gamelan has been mapped into the

Western staff. In Chinese music, sheet music is written with numbers,

letters, or native characters to represent notes in order.

It's not The Muse's purpose here to enumerate or explain any of these

notation systems in detail. Rather, by touching on a few such systems, the

Muse hopes to make a single point, namely that a large number of widely different music notation systems

have been devised, many of which are now in use. This is to be expected,

since music is so important to people all over the world.

Why are there so many different notation systems extant? Why are so many

needed?

Many factors have caused

cultures, scholars, or musicians to develop their own notation

systems rather than to adopt or adapt preexisting ones. Many factors have

caused them not to abandon their own notation systems in favor of a standard

notation scheme or in favor of the scheme of another culture or nation. Many

factors cause new notation systems to be developed as time goes on. Here are

but a few:

- Worldwide communications are only a relatively recent development;

musical notation systems have existed for a very long time. At the time a

particular culture's notation system was evolving, that culture may have

been unaware that other cultures possessed notation systems that could have

been adapted to meet its needs.

- A culture's musical instruments may be very well be unique. theymay

possess different ranges, tones, fingerings, or other musical qualities that

cannot be expressed in another culture's musical notation system.

- One culture's musical style may call for a correspondingly unique

notation system that can express its individuality.

- The symbol system of a culture may be incompatible with that of another

culture. Oriental symbol systems, for example, do not lend themselves to

Western notation.

- Different musical notation systems serve different purposes. For

example, one system may be designed to make the symbols easy to learn while

another system may be designed to use symbols that facilitate musician

practice sessions; other systems may focus on using as few symbols as

possible or on controlling a computer.

|

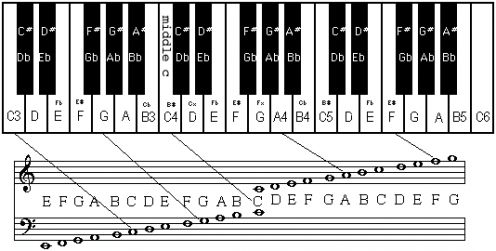

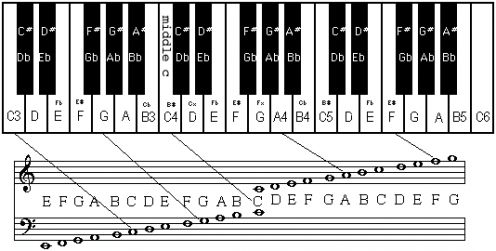

| A notation system will reveal the relationship musical

notes written on paper and notes played on an instrument. Here we see the

relationship between the notes on a 5-line stave and the notes on a piano

keyboard. |

The modern Western notation system is a de facto standard that is taught

and learned by musicians throughout the world, who pass their knowledge to each

other, from school to pupil, teacher to pupil, and generation to generation.

But it is not the be-all and end-all of notation systems, even among

musicians for whom Western notation is primary. Just as some people speak or

write more than one language, some musicians for whom modern notation is

primary play and write in more than one musical notation system.

more about modern Western notation

This feature is continued on the next three pages.

- Visit the pages that follow to further explore modern musical notation

of the Western Tradition:

click here.

—Page

1,

2,

3,

4—