How are expository and creative writing related? Can expository writing

be fictional? Can non-fictional writing be creative? Can fictional writing

be expository?

Many people inaccurately believe that, to be valid, expository prose writing must

always be objective, nonfictional, and non-creative, no matter what its

purpose; otherwise it defeats its primary reason for existing, which is to

factually inform. They hold this belief because they believe that any other

kind of expository prose distorts the facts of the matter by being

subjective or fictional.

These views are correct, as far as they go: if a written work's primary

purpose is to convey facts, there is no place for fiction i it because

fiction distorts or overlooks pertinent facts.

People who object to creativity in expository prose writing are correct

if by creativity they mean the power to introduce errors, imagine falsities,

or invent other kinds of unfactual things. Whenever the primary purpose of a

written work is to convey factual information, creative, nonfiction writing

is unquestionably the correct style of writing to apply.

There's absolutely nothing wrong with expository prose writing that's

objective and non-fictional; writing genres that possess these

characteristics are among some of the most important ones in the world and

without them it would be virtually impossible for society to get along. They

include newspapers, magazines, scientific reports, term papers, use and care

manuals, historical accounts, engineering documents, "how to" books, and

many, many more document varieties.

But people who totally reject creativity in expository prose writing are

dead wrong if by creativity they mean imaginative originality of thought or

expression. There's always room for creativity in writing of any kind so

long as creativity doesn't introduce facetiousness, exaggeration, or skewing

of facts, data, or other information.

There's also room for subjectivity in expository prose writing whose

primary purpose is to inform. Authors can and do introduce and maintain

subjectivity in expository prose writing by identifying their personal

points of view and opinions and by clearly separating them from the facts on

which they base them. If they write lucidly, exercise an honest discipline,

and make sure to include all relevant information, there's little reason to

fear that their expository prose works will distort or skew facts or data.

One only has to consider the writing genre known as the essay to confirm the

the fact that this can be done.

On this page, The Muse attempts to demonstrate that

this belief is inaccurate; while many expository prose pieces do belong to genres that are

objective, non-fictional, and non-creative, many other valid expositional

genres do not possess these characteristics.

into this kinds of writing is one of the Artificially limiting

expository prose writing to objective, nonfictional writing condemns it to

being uncreative. it detrimentally limits the scope of expositional

prose writing because it too narrowly conceives the nature of information

and the function of exposition.

The Muse is not calling these genres exceptional because they're rare or

extraordinary, or even because they're exceptionally good, which they may be

(The Muse is not passing judgment on them now). They're exceptional because

they're not exceptions to The Muse's definition of the concept of literary

genre. [link to genre def and def of exceptions]

To avoid possible confusion, The Muse Of Language Arts strongly suggests

that you consult list of terms you will find at The Muse's page titled Terms

Related To The Subject Of Expository Prose Writing. The terms will help you

avoid confusion regarding the nomenclature used in

this discussion of expository prose creativity:

click here.

A work doesn't have to be dull or plain just because it's primary purpose

and unintended result is to

distribute non-fictional information. An author's treatment of subject

matter, his writing style, or his personality can be so unusual, forceful,

or skillful—and he can make so great an impact on

devoted readers, or on a prominent best-seller list, or on an

influential social group—that his non-fictional

creative works forge an entirely new genre. This can happen even if the number of authors who contribute

to the new genre is small (or even

unique), the body of works they produce is small, or the audience is few in

number.

Lest you believe that non-fiction expository prose writing cannot be creative, consider

three different works by the 20th century American writers Truman Capote, Jack

Kerouac, and Hunter S. Thompson, all written in the main with exposition in

mind.

These three authors and their works are among those that illustrate how

and why non-fiction expository prose writing can

not only be objective, novel, and brilliant, it can be subjective,

fictional, and artistically creative, all at the same time. It can

excite, be interesting, and be fresh. Non-fiction expository prose works can

be replete with factual content and heady new ideas without suffocating; yet

they can inspire, stimulate, and motivate. And they can do these things so

well and to such an extent that they can be vehicles for creating and

establishing new literary

genres.

|

| Truman Capote |

frankenstein

If you think that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's 1818 novel

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a horror story, think again.

It's more science fiction than horror. In fact, although it combines

elements of the Gothic novel, the Romantic Movement, philosophy, and the

horrific, most experts classify it as one of the earliest true science

fiction stories.

Although today the Frankenstein story has the status of a legend, it

came to her one night in a dream. It's a pure invention, a dream that grew

a legend, a tradition, a cultural myth. it's so much a myth that some

people who haven't read the story incorrectly believe

How did Shelley's dream grow into a legend?

Victor Frankenstein has a name. One of the things that bothers the

monster is that his creator didn't care enough about him to give hime a

name.

why phisosophical? Raises issues: Does man have the right to create

life? if man crates life, does that make him Godlike? If so, does he have a

moral responsibility for the life he creates? Does he have a moral

responsibility to take care of his creation?

legend is a dream

source of horror--plays, movies, books

relation to Jules Verne, et al

product of her creative genius: personal innovation + same stirrings

as--Industrial Revolution, rise of science and engineering

The ability to write creatively does not have to be inborn, although

a lust for living, a natural creative bent, and a thoughtful, analytic, innovative

approach to answering big or little questions helps greatly.

Writers often find external incentives to write creatively if they live

in a period when society is undergoing fundamental changes that they

strongly embrace, if they identify with a great artist whom they believe to

be a kindred spirit, or if they affiliate with an artistic movement toward

which they feel strongly attracted, especially a revolutionary one.

Notice that, like a giant magnetic pole, these kinds of external-world factors can,

if a writer responds to them powerfully, exert powerful

forces on a writer's creative juices if he possesses a powerful positive or

negative internal pole.

Creative writing takes place most often when an author has a strong desire

to see and feel external worldly forces differently from the way other

people see them and when he is highly motivated to

express his unique viewpoint as well as he can. If a writer is on a personal

mission...if he has fire in the belly...if he burns with a thirst to reform or to awaken some aspect of

society or human nature...then he inwardly experiences a font of ideas, emotions,

and words.

This fount springs forth spontaneously, naturally, without straining;

it's the easier part of the creative writing process. The

rest of the task is a relatively painful and laborious one in

which the writer tries to accurately convert these honest, inward,

subjective apprehensions to outward, objective

expressions and to capture them on paper.

Truman Capote—the nonfiction novel

In the last century there arose another, even more compelling example of

the nexus between creative writing and exposition than had come from the brilliant essay writers of previous centuries.

Truman Capote, American

novelist, short-story writer, and playwright—primarily a writer of

fiction—who was at a point later in his career when he

had became preoccupied with journalism, developed a journalistic approach to the novel

which he called the nonfiction novel.

In 1965, Capote published what is perhaps his

best-known work, In Cold Blood, a chilling account of the real-life multiple

murder of a Kansas farm family committed by two young psychopaths. Capote spent six years

interviewing the principals in the case before publishing his book.

The book is the story of actual people and events told in the dramatic

narrative style of a novel and also in the reportage style of a newspaper

account. The story is told from the points of view of different

“characters,” while the author carefully avoids intruding his own comments

or distorting fact.

Capote's goal was to expose the nature of this kind of crime and the

madness behind it as if his book were

an objective, expository treatise on the criminally insane or as if it were a newspaper account of a

crime, at the same time projecting the emotional impact, expressiveness, and depth

of insight usually associated with an important fictional work.

He had deliberately forged a new non-fiction genre whose key concept was

that it was based on expository prose.

Jack Kerouac—spontaneous prose

On the Road is a novel by Jack Kerouac

that he based on a series of motorcycle road trips that he and his friends took across middle America early in 1950 and before.

Although it is represented to be a work of fiction, Kerouac's book is

based on fact and is largely autobiographical. It is written in the style of a roman à

clef.

A roman à

clef, sometimes called an historical novel, is a novel that represents actual events and characters under the

guise of fiction. The prose narration of a roman à

clef is fictional but the events and characters it depicts are real.

Details of events and characterizations may be fictional to an extent that

depends on such factors as the novelist's narrative treatment, the degree

to which facts are available and are incorporated by the the novelist, and

the extent of fabrication to which the novelist is willing to go to make

his points.

The book's hero is really Kerouac; its character's are his real friends—his

traveling companions—and the people they meet

on their adventures. Characters and events are only mildly disguised, if at

all. Kerouac is the

narrator and he speaks in the first-person; the book's voice is his.

An account of his post World War II adventures and

exploits, the book is filled with offbeat tales and out-of-the-ordinary

events concerning jazz, poetry, and drugs. Although he changed many of the

details of their names, characters, personalities, attitudes, experiences,

behavior, and places, many of the people and events have real life

counterparts. Primarily, only the names have been changed to protect the

innocent and to shield the author and publisher from lawsuits.

|

| Kerouac on the road |

In the late 1940s, prior to writing On the Road in 1951, Kerouac

had invented and introduced the term Beat Generation to his

immediate associates, and subsequently to the public at large, to describe

an underground anti-conformist youth movement underway and gaining momentum

in New York. Initially he applied the term beat to describe people

who were sick-and-tired or beaten down; later he expanded his notion of a

beatnik to describe upbeat characteristics such as upbeat or

beatific, which he associated with the expression on the beat

that was well-established and popular in jazz music at the time.

One of the Kerouac's major objectives in writing the book was to inform,

influence, and spread Beat principles and ideas to an audience that

was larger than those in New York that he had previously dubbed beat.

The book was his way of defining, creating, and spreading the ideology and

value system he had adopted and made his own, that of the so-called Beat

Generation.

Kerouac is considered by many to be the father of Beat social movement. Kerouac's book not only inspired America's youth to become beatniks, it

helped produce a group of American post-WWII beat writers of the 1950s who

followed the book's ideas about the right way to live and who adopted and

emulated Kerouac's writing style. It and the Beat movement it

fostered led to the

Hippie movement that followed in the mid-1960s; and the term hipster,

which later was used to denote a hippie, was initially coined to describe

the pre-hippie beatniks who had moved into San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury

district.

Kerouac's writing style, which he called spontaneous prose, is a

literary technique similar in some respects to the stream of

consciousness writing style. In it, you may see a resemblance to the

writing style of James Joyce, whom Kerouac admired and attempted to follow.

His technique for writing non-fiction prose consists of about ten

factors, principles, or methods. For the most part, the following textual fragments are

quotations; they're paraphrases

taken from Kerouac's own description of how he wrote and what he wrote

about:

- Undisturbed flow from the mind of personal secret idea-words, blowing

(as per jazz musician) on subject of image.

- No periods separating sentence-structures already arbitrarily riddled

by false colons and timid usually needless commas-but the vigorous space

dash separating rhetorical breathing (as jazz musician drawing breath

between outblown phrases).

- No pause to think of proper word but the infantile pileup of

scatological buildup words till satisfaction is gained.

- Modern bizarre structures (science fiction, etc.) arise from language

being dead. Follow roughly outlines in outfanning movement over subject,

as river rock, so mindflow over jewel-center need (run your mind over it,

once) arriving at pivot.

- If possible write "without consciousness" in semi-trance (as Yeats'

later "trance writing") allowing subconscious to admit in own uninhibited

interesting necessary and so "modern" language what conscious art would

censor, and write excitedly, swiftly, with writing-or-typing-cramps, in

accordance (as from center to periphery) with laws of orgasm, Reich's

"beclouding of consciousness." Come from within, out-to relaxed and said.

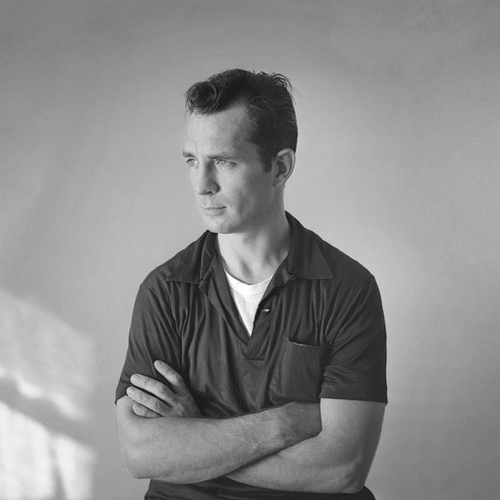

|

| Jack Kerouac |

This phraseology may seem offbeat to you, but it fits the beat

mindset; it's decidedly Beat.

Many poets, writers, actors, and musicians were attracted to Kerouac's

writing style, subject matter, and value system, and were strongly

influenced by On the Road. Among them are Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison,

and Hunter S. Thompson. (The work of the last of these three artists,

Thompson, is examined next on this page.)

Spontaneous prose has evolved into more than just a writing style; it

has become a literary genre.

Judging by the preceding description, it should come as no surprise to

hear that Kerouac is considered a literary iconoclast, a title that is

shared by William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and other Beat Generation

pioneers. He had deliberately created the genre in which he and these

others wrote in order to achieve his societal agenda; it was a genre that probably

would have failed his purpose had it not been based on non-fiction

expository prose.

Hunter S. Thompson—Gonzo journalism

Thompson's 1971 book titled Fear and

Loathing in Las Vegas is an account of

a trip he took to Las Vegas with his real-life attorney in his capacity as a

professional news reporter, on an assignment for Rolling Stone

magazine. There he covered a real life convention at a famous hotel and

gambling casino that was sponsored by the National District Attorneys Association's

Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.

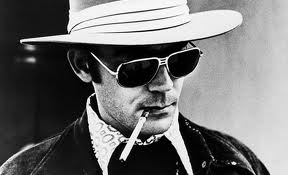

|

|

Hunter S. Thompson |

As with Kerouac's On The Road, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

is portrayed as a fictional novel, but the book is based on true people and

events and

is largely autobiographical. And, as with On The Road, Fear and

Loathing is written in the form of a roman à

clef or historical novel; it's a novel that represents actual events and characters under the

guise of fiction.

Like Kerouac, Thompson hides the true identities of the events,

characters, and institutions he is reporting on by changing their real

names, most likely in order to avoid lawsuits; but unlike Kerouac, who published under

his real name, he clouds his personal connection with the book by

publishing under a pen name.

Nevertheless, those in the know understand that the novel's hero, named

Raoul Duke, is

really Thompson and that the book is a true-to-life accounting of what

really happened to Thompson and his attorney, named Dr. Gonzo in the book, at the convention. Thompson is the book's

narrator and it is he who is speaking to us in the first-person, telling us

about his adventure; the book's voice is his. And those in the know also

understand that the hero is covering a convention that in its essentials is

virtually identical to the real convention that Thompson covered for the

Rolling Stone.

On the Road and Fear and Loathing are similar in several

respects, but they differ when it comes to their focus. Kerouac's focus is

on his personal adventures and how they illustrate and justify his

lifestyle. It argues in favor of the case that his lifestyle should be a

role model for others.

But Thompson's focus is farther afield; it's on moral and ethical ideals

and on how America has departed from them.

Normally, most people expect newspaper reporters and magazine writers

like Thompson to report on events

and people factually and objectively; this kind of report would be required by any

managing editor striving to maintain editorial integrity.

But that's not the case here. Thompson's book is not about an article

that he needed to write for Rolling Stone about a drug convention; nor is

it an article for Rolling Stone that he adapted and expanded into a fictional novel.

Fear and Loathing is a fictionalized account of what really happened to Thompson on his trip to Las Vegas that

embodies and expresses his personal perspective on life in America.

Thompson has his hero talk to us in the first person, as though he's

recounting what took place. Writing this way, Thompson makes us feel as

though we might be listening to the hero tell us about his trip while seated in his armchair

in front of his fireplace, sipping cocktails and rubbing his dog while

recounting what

happened on his last assignment.

That might be the way the real Thompson would tell us his real Rolling

Stone story. Thompson is

telling us the truth about what happened to him on his Las Vegas assignment.

what this book is about

During

their trip to Vegas, the hero and his attorney-companion undergo a

variety of adventures, some before and some during the convention, others

afterward and elsewhere. Along

the way they indulge in one adventure after, some that border on dangerous,

others that are funny, and others that are boring to the characters (but

are always interesting to the reader). They take risks; they experience a

mixture of good and bad luck. All their interactions with people and

things expose

raw human nature and the nature of life and living as it really is.

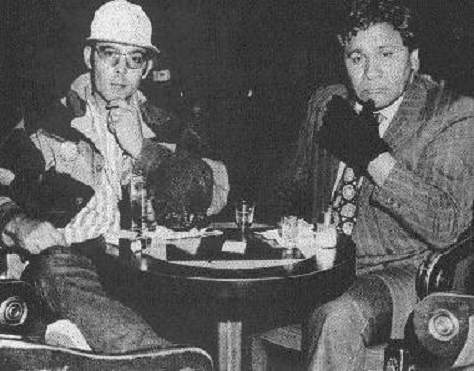

|

|

Thompson (left) and Oscar Zeta

Acosta (Thompson's real-life attorney) |

As the two main characters go round and round on their adventures they pig out.

They

consume large quantities of grass (marijuana),

mescaline, acid (LSD), cocaine,

and a variety of

uppers,

downers,

screamers,

and

laughers, intermixed and interspersed with generous quantities of tequila, rum, Budweiser, raw

ether, and two dozen

amyls. They cheat others and they are cheated by others.

Low life and high life; they're both there. But don't get the wrong idea; this is not a simply retelling of the

hero's escapist sexual, carnal, immoral, and amoral self-indulgences, and

those of his traveling companion. The hero's assignment

is to prepare an article that reports on what he describes as a police narcotics

convention, but something else is preoccupying his mind—the

American Dream.

The hero looks around himself for the American Dream, but doesn't find

it. He's disgusted by what has happened to it. He seeks the good in

America and its culture but finds little left to recommend it.

The hero's adventures bring to mind the under- and above-ground

anti-conformist, anti-authoritarian, anti-establishment movements that were extant in America

in the 1950s and '60s—the counter-culture

movements of the beatniks and hippies and the anti-war demonstrations that

were aimed at bringing home the troops. He believes that the rationale

underlying these movements and their goals were worthy but that their

hopes and dreams went awry.

What happens to the hero on this trip—everything

and everyone he sees about him—prove it; they illustrate and

justify his disillusionment. He's disgusted, sickened, and disheartened.

Is Fear and Loathing a true account of what happened to Thompson

in Las Vegas?

Yes and no. At first the reader is mislead by the book. It turns out

that the story is not about a real convention as it seems to be at first.

It's only secondarily a news report about a drug convention; it's mainly a description of what

went wrong with the American Dream.

Although based on real events, Thompson's account of what happened in

Las Vegas departs from the actual events in its details. It presents

itself as a true-to-life account, but it's not news reporting in the

conventional sense; it's not news. Thompson distorts, avoids, exaggerates,

overlooks, and

discolors facts in order to make his ideas known and his feelings

felt. The story the hero tells allows you to see for yourself what has

gone wrong and to share in his disappointment.

From a literary point of view, Thompson writes a well-told fictional story

that's based on actual facts. But since his story is a mixture of fact and

fiction, he must construct it creatively. He departs from fact when

necessary to make his points. He adumbrates and

selectively omits some events; he shortens and condenses dialog; he edits

narrative to maintain clarity and pacing and to avoid inducing boredom.

But when it comes to his true subject—The

American Dream—he's as honest, complete, and true-to-life as

he can be.

|

| An Older Thompson |

about gonzo journalism

Fear and Loathing is the first major work written in a style

today

known as Gonzo journalism, a writing style which Thompson invented.

What is Gonzo journalism? Gonzo journalism is journalism that takes

place when the journalist (the reporter) is an actual participant in

the live action that is being reported on. Gonzo journalism tends to favor style over

fact to achieve accuracy and often uses personal experiences and emotions

to provide context for the topic or event being covered. It rejects the

polished, edited news product favored by newspaper editors and strives for

a more gritty approach. Use of direct quotations, sarcasm, humor,

exaggeration, and profanity is common.

Gonzo journalism is personal, not objective. It's purpose is to report

honestly on political or moral issues, or on similar issues; but it favors

writing style as a means to convey truth even if it becomes necessary to

sacrifice accuracy to achieve its goals.

Gonzo journalism and gonzo journalists are resolute, courageous, and

plucky. They tend to write abut coarse personal experiences and emotions

as a means to provide context for the topic or event being covered. They

avoid the polished, concise prose and objective reporting normally

expected from newspapers and editors, and they don't hesitate to employ

quotations, sarcasm, derisive humor, exaggeration, or profanity to help

them drive their ideas home.

A Gonzo journalist involves himself in the action

to such a degree that he becomes the central figure in his story; he

personally acts out his story, sometimes literally. He interacts with and

behaves like the people he is reporting on.

This kind of journalism stands in sharp contrast to traditional

journalism, which stresses that events should be reported with total

objectively, minimal use of words, and without personal involvement by the author, except perhaps for

a byline.

|

| Johnnie Depp, hero in the movie version of

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas |

Thompson, the Gonzo journalist

The term Gonzo in Gonzo journalism was not invented by Thompson; it was

conceived by

a prominent newspaper editor who had seen and admired an article by

Thompson published prior to Fear and Loathing. He described the

piece to Thompson as "pure Gonzo," explaining that a Gonzo is a

creature of South Boston Irish slang which he defined as the last man standing after an

all-night drinking marathon.

Thompson immediately saw that this idea applied to him; and it fit his

writing style to a "T." He like it. He soon began describing his

reportorial writing style as Gonzo journalism and signed his

published works as Gonzo. His personality, writing style, lifestyle, point

of view, and values all seemed to match the name, and for the rest of his

life he frequently referred to himself as Gonzo when he was with others.

Thompson's writing style was born out of a combination of his

personality, lifestyle, and working habits:

Thompson saw himself as a novelist but earned his living early on as a

writer until he could break into literature. He most admired Ernest

Hemingway from the start, for his adventurous life as a war

correspondent, for his writing style, and for his novels. He emulated his

lifestyle as a sportsman and womanizer and he tried to live the kind of

life that would qualify him as a legend in his own time, the way Papa

did. In fact, Thompson's life was so modeled after Hemingway's that he

committed suicide the way Hemingway did.

Hemmingway's influence was strong in Thompson's life and writing

because he demonstrated career and personality traits that Thompson

admired. But Thompson also demonstrated characteristics that were his

own.

He was possessed by himself and his own moods, attitudes, and

opinions. He felt a psychological necessity to write with his own voice,

to write as himself; and he wrote as he spoke, in the first person. This

meant that he had to narrate what he wrote.

He suffered from a compulsive need to make himself heard instead of

stepping out of the way, as most newspaper men and women do when they

report events or subjects objectively. This drove him to take a

subjective approach to reporting.

Thompson knew how to put words on paper and to craft objective

newspaper articles the way you might expect a competent

newsman to do, but he personally favored a use of language was more vibrant, expressive, penetrating, and colorful

than most factual newspaper reporting. He had an active, innate sense of

humor, much of which was sardonic, and the humor didn't stop; he couldn't

suppress it. These qualities affected and distinguished his style.

He was personally disillusioned, disappointed, and embittered by the

political, social, and ethical conditions he saw at work around him—by

the way his world worked. These sentiments and values affected his

subject matter, tone, and point of view.

Further, he had other professional pursuits and his work required

extensive, time consuming travel. He indulged himself in idle diversions

and pursued hobbies such as guns and hunting. He smoked incessantly and

underwent wild and unremitting bouts with booze and stronger stimulants

which resulted in a chronic mental condition that in

polite circles is called writers block. Instead of setting

aside quiet hours that were sufficient for him to fashion a conventional, carefully-crafted,

polished magazine or news story as most reporters might try to do, he

would frequently put off working on a new piece for publication until it

was dangerously close to its due date.

Under conditions like these—with a

deadline looming but with no copy to submit—he

would approach the challenge of drafting a new piece in a state of sheer desperation;

he would undergo repeated, suffocating, hobbling anxiety attacks that

would cause him to digress even further.

Unable to put last-minute words on paper, he would finally give up in

a panic, rip pages out of his

notebook, and send them in for publication, leaving it to rewrite men to

convert his notes to a piece suitable for publication.

For their part, publishers knew that his pieces were so good—that

his ideas, content, characterization, and writing style were so

powerful and important and that his audience was so

large and hungry—that they allowed him the leeway to work in this

way. That's why Thompson's writing sounds more like his personal notes

about something he's witnessing "now" rather than like an anonymous

reporter's objective account about something that had happened to some

third party in the past.

That's not to say that Thompson couldn't write a competent conventional

news story or that he didn't write well when

circumstances allowed; he cooperated with publishers when feasible. Fear and Loathing

attests to this fact. He could

draft punchy, understandable sentences and paragraphs that were economical, crisp, lean

and clean, neat,

incisive, logically organized, thought-laden, provoking, and to the point. His dialog was concise,

conversationally interactive, and believable. His references to

real people and events were sharp, current, and direct; and he could name real

people and cite real events when it suited him.

birth of a genre?

Thompson lived what he wrote and he wrote what he lived. Thompson is the

hero in Fear and Loathing and the hero in Fear and Loathing is Gonzo.

Gonzo journalism was born out of Thompson's values, his own personality,

the social conditions in which he found himself, and the stressful circumstances under which he lived and wrote.

It took a man of these characteristics to create the new kind of

journalism we call Gonzo journalism.

Despite criticism—perhaps partly because of it—Thompson

soon incorporated his Gonzo journalism news reporting style

in everything he wrote, from "factual" magazine articles to literary works like the novel,

Fear

and Loathing.

Thompson's new and insightful writing style became noticed by editors

soon after he started using it. Some liked

it but others were repelled by it. That didn't deter him. Since he believed that journalistic objectivity is a myth, he saw no

professional or ethical problem with injecting subjectivity into journalism if it helped bring out

underlying truth. He continued to write about subjects that were important

to him, about the ideas and ideals he valued, at whatever cost.

These attributes appealed to his reading audience. His Gonzo writing

style soon caught on with

readers and with other writers. It wasn't long before Gonzo journalism

began to evolve into a genre.

Eventually Gonzo journalism became a style of writing that is generally

accepted by most readers, even if it's still avoided by publishers who

report hard news. It's a style that elevated the importance of "telling it

like it is." Today it's classified as a sub-genre of another subjective

journalism style called New Journalism, which was developed in the 1960s

and '70s by

authors like Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, and

others.

|

|

—note— new journalismNew Journalism is a genre that does not conform to the dispassionate and

even-handed paradigm historically associated with traditional journalism.

Works in this genre not only report facts, they

attempt to convey feelings and emotions by incorporating literary devices

usually encountered in fictional works like novels.

New Journalism is a creative non-fictional

genre in its own right. It not only reports facts, it establishes character, explores

motivation and thinking, and employs other techniques normally associated

with novel writing. |

Thompson died in 2005 at the age of 67. Since then his contributions

have not only influenced journalism; his life and work have affected the

collective conscience and the collective unconscious of society as a whole.

His ideas and approaches have shown up in novels, documentaries, and works

of art. Many websites are devoted to Thompson; and his ideas about

reporting news and journalism have even affected the way ordinary people,

not professional writers or journalists, express themselves on blogs and at web sites like Facebook

and Twitter.

Umberto Eco

[creating genres--still going on]

The Muse suggests that you ponder these questions in the light of the

works contributed by Capote, Kerouac, and Thompson: