|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the nature of creativity in writing Here The Muse Of Language Arts

explores the nature of creative writing. Here The Muse Of Language Arts

explores the nature of creative writing.

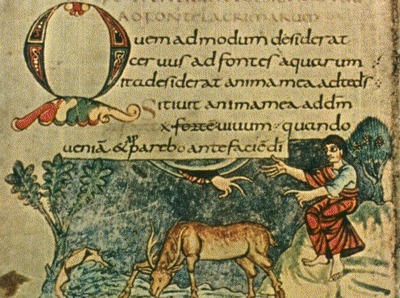

That which is creative results from originality of thought or expression; it's imaginative or original. From a literary perspective, creative writing is any writing that is the product of original composition, where composition is the art of putting words and sentences together in accordance with the rules of grammar and rhetoric. Creative writing is the act or process of producing a literary work. Creative writing includes any writing that goes outside the bounds of normal professional, journalistic, academic, or technical forms of literature. Writing is usually recognized as creative when its emphasis is placed on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes. Examples of the kinds of works that can be creatively written include literary forms such as novels, biographies, short stories, and poems. Creative writing is not restricted to fictional writing, however, as many readers believe. For example, autobiographical and biographical writing can be very creative even though a biography is a written account of a person's life, an organization, a society, a theater, and animal, etc. Subjects like these are drawn from real life, so they must be treated authentically, in a nonfictional vein. Thus both fictional and nonfictional works can be creatively written. As with many other literary terms, the definition for what it means to say that a written composition is creative is rather loose. For example, consider feature stories. A feature story is a newspaper or magazine article or report of a person, event, or an aspect of a major event. Feature stories often have a personal slant and are written in an individual style. Personal slants and individual styles are aspects of composition usually associated with creative writing. Technically, then, it's possible to considerer feature stories a form of creative literature, even though strictly speaking they fall under the literary category of journalism. Academics and other teachers have their own classifications for creative writing. Typically they separate creative writing classes and topics into fictional prose and poetry on one hand and nonfictional writing on the other hand. In fiction and poetry classes their focus is on teaching students how to write in an original style as opposed to imitating preexisting genres. Academics also tend to separate the teaching of writing for the screen and stage (screenwriting and playwriting) from each other, as well as from other kinds of creative writing, even though they both definitely fall under the category of creative writing. In a general sense, the term creative writing is a contemporary process-oriented name for what has been traditionally been called literature, an activity and a field of authorship that includes a variety of genres.

the nature of literary creativityWhat's literary creativity? At first, creativity, creative writers, and creative literature may seem to be entities that are hard to put one's arms around. If you write, exactly what does it mean to say that you demonstrate creativity or write creatively? Why are you creative? What makes you so? If you're an author who's produced a body of creative literature, exactly what does it mean to say that your works are creative as a whole? Why is one body of work more creative than another that you've produced that is not as creative? Or why is your work less creative than another author's body of work? In large measure, creative writing is difficult to define because an author's creativity and that of his work exhibit numerous abstractions, vague concepts, and inexplicit qualities that are hard to pin down clarify, or judge. There's no one clear cut formula that defines the nature of creative writing generally, and there's no special way to write that guarantee's that creative work will result. In other words, the properties that make any literary work creative are amorphous: they evince no definite form or specific shape, and they show no particular character, pattern, structure, or composition. In fact, the world's body of creative writers and the great literary works they have generated possess greatly divergent literary properties, in some cases opposing properties; yet they all seem to fit the bill one way or another. Ironically, one of the properties that characterizes this mass of creative authors and their works is divergence itself; that is, the more unique and original an author or his works, the more creative they are considered to be. Despite all this intangibility, let's take a swipe at defining creative writing anyway. Instead of procrastinating, if we do this now perhaps later we'll be in a better position to refine what we come up with. Here are a few preliminary albeit rough ideas for what it means for an author to be creative or to write creatively. They're not all specific or unique to writing, but as a group they all apply to one extent or another:

The Muse Of Language Arts attempts to elaborate and to narrow these definitions in sections that follow. what is creative writing—really?

For example, to keep their discussions simple, many literati—those who specialize in literary subjects like these—equate creative writing with nonfiction writing. According to them, if it's creative writing, it's fiction, and if it's nonfiction, it's not creative writing. They exclude nonfiction writing from creative literature. They take the inverse position as well. If its fictional writing, it's creative; if it's nonfictional writing, it's not creative. But actually, among themselves they acknowledge that creative writing is not exclusively fictional, and that not all fictional writing is creative. When pressed to explain, they usually don't hesitate to point out that there's more to the subject than appears on the surface. As The Muse will soon make clear, it may not at first be apparent that the creative writing definitions cited in the preceding section actually span virtually any kind of writing, even nonfiction writing, so long as nonfictional writing ventures outside the bounds of normal disquisition. Thus creativity may even be exhibited by professional, journalistic, scholarly, or technical forms of writing, depending on how they are done. In actuality, whether or not it's fictional, a piece of writing is creative if it emphasizes narrative craft, character development (when character and personality are legitimately involved by subject or purpose), and by extensive use of literary tropes. In the sense of the word creative cited above, creative writing includes virtually any kind of writing, even nonfiction, so long as it ventures outside the bounds of normal disquisition. Thus it may include professional, journalistic, scholarly, or technical forms of writing. Whether or not it's fictional, a piece of writing is creative if it emphasizes narrative craft, character development (when character and personality are legitimately involved), and extensive use of literary tropes. Notice that virtually all literary and other kinds of fictional works contain significant passages that are nonfictional. For example, even novels, which by definition are works of fictional narrative prose, frequently employ nonfictional passages to introduce relevant facts that describe and establish credibility, background, situation, back stories, and for many other purposes. The fact that novels include nonfiction doesn't automatically mean that they are uncreative. As another example, historical novels are fictional works based on real people or on actual people, locations, or events drawn from history. Poetry provides yet another example of why neither fiction nor nonfiction can legitimately be equated either with creativity or with non-creativity. A poem is a literary work in metrical form; it sings; it's rhythmical; it's spiritual and aesthetic; it's a highly creative construct. Further, poetry is a literary form that is musical, elevated, and beautiful. Many poems, especially those dubbed lyrical, are outpourings of a poet's personal thoughts and feelings; they seem to express a poet's spontaneous and direct emotions and reactions. What other form of literature is more artful, more intensely imaginative, more of an outpouring of an author's own thoughts and feelings than is a great poem? Yet many epic and dramatic poems tell tales that are written at least partly to set forth, explain, and interpret nonfictional information such as historical events, real people and places, and actual things. Some convey facts and figures, describe inventions, explain cause-effect relationships, and much more that is not fiction. Yet the subjects of many poems like these are based on historic fact, real persons, places, or events. Some such poems even seem to gain greater power because the poet is reacting creatively to real rather than to imaginary happenings. Witness poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Paul Revere's Ride, affectionately known as the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere; witness also ancient Greek tragedy, much of which is a religious outpouring about mythical events believed at the time to be literal, historic truth. Is all creative writing literary? Is all literature creative?Most literary works are structured in accordance with the rules of one or another specific literary form—for example, works of art such as poetry, novels, history, biography, and essays each have their own purposes, forms, styles, and ways to be written. Further (and very important), to be called literature in this higher sense of the word a work must express ideas of permanent and universal interest. But this is not the only kind of literature there is, by any means. The

term literature has more than one meaning.

Any kind of printed material also can be called literature if it can be written down or printed, has a purpose, and makes sense. This kind of literature includes such forms and writing styles as circulars, leaflets, technical manuals, advertising billboards, or handbills. Although literary forms like these tend to have specific writing structures and writing styles, they don't necessarily have to be structured or written in any particular way; their purpose defines what they are. And very important, they aren't intended to express ideas of permanent and universal interest. In order to distinguish these two different kinds of literature from each other, The Muse Of Literature reserves two ways to refer to them. The Muse refers to the first kind, the one that expresses ideas of permanent and universal interest, as Literature spelled with a capitol "L;" and The Muse refers to the other kind, the one that does not express ideas of permanent and universal interest, as literature spelled with a lower case "l."

Cognoscenti who look up their noses at literature regard Literature as offering authors the opportunity to write creatively, and regard literature as not offering authors this opportunity; and the public tends to follow them in their wake. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Ingenuity and imagination are pervasive talents that follow us into almost all corners of human endeavor. Thus, an author who writes creatively does not necessarily have to produce writing that's Literature in the formal sense of the word; literature will do. It's vital to realize that almost all kinds of writing offer authors the potential to be creative in one way or another, whether they write Literature or literature. The literature of a science like ornithology, for example, can be creative despite it's factual, unemotive, and unaesthetic character. Literature that deals with a particular scientific subject like ornithology can be creative, as can tourism and travel guides, magazine articles about Hollywood, or news articles about politics, people, and space travel, and many other forms of authorship.

In summary, what most people mean by creative writing depends on their definition of the word creative. Definitions like these can be misleading. In its broadest sense, the act of writing creatively actually demands (and results from) a certain kind of approach to writing and an attitude toward writing rather than from the definition they apply or on adherence to standard or conventional artistic formulas such as predefined literary forms, choice of writing mode, or style of expression. Indeed, at core creative writing is anti-formulaic; it's the opposite of writing that conforms to rules, regulations, and conventions. In is in this broad sense that The Muse Of Language Arts applies the term creative. creative writing and non-creative writing comparedThe distinction between creative writing and noncreative writing is stark. Hopefully, this comparison between the two forms of writing will help shed light on the nature of of creative writing. Is there any truth to the notion that, taken as a whole, the world's entire body of fictional literature is more creative than the entire body of nonfictional literature? Yes. However, that doesn't mean that fictional literature is always creative, or that nonfictional literature is never creative, as many people seem to believe. They base this view on the fact that fictional authors invent the things they write but nonfiction authors don't invent because they stick to facts, plain and simple. This view is misguided. There's no objective way to measure creativity; there are no such things as creativity units and there are no creativity meters for measuring it. But there are good reasons to believe that, taken as a whole, the entire body of fictional literary works is more creative than the entire body of nonfictional literature. Why? In part, this posture is credible because the process of writing fiction is itself inherently more creative than the process of writing nonfiction. Authors who write fiction must invent the sham facts, people, events, objects, and other components that make up their works, a task that's more challenging than simply referring to, conveying, or writing about actual facts that come from other sources. The act of writing fiction pressures authors to drum up the accounts, characters, stories, subjects, themes, and other literary elements they write about. Just being able to to set words on paper forces fiction writers to think things through, imagine, and innovate. Also, many kinds of fictional works tend to express symbols and kinds of abstract concepts that don't arise in connection with descriptions of objective facts. Fiction writers like to write about personal and original observations and reactions to their inner lives and outer surroundings. These kinds of topics demand more creative forms and styles of expression. Although fictional writing contains significant amounts of invented (fictional) information, it's critical to realize that it also contains nonfictional information. If it didn't contain actual (nonfictional) information, there would be nothing for a writer to base his fictional creations on. How could he develop fanciful characterizations of fictional people or places that readers could recognize and understand if there were no real people or places in the world on which to base them? If a writer's fictional inventions were totally his own, they would be unfounded; readers wouldn't recognize them or understand what they mean. The same sort of premise holds true for nonfictional writing, but in an inverse way. For the most part, non-fiction writers describe real-world facts given to them by others or information they dig up for themselves by doing research; to the best of their ability, they do not present facts unless they are actually present and correct. Nonfiction writers do not manufacture information out of whole cloth with their own imaginations. Nevertheless, although nonfictional writing primarily contains real factual information, it's critical to realize that it also may contain fictional information. For example, it should come as no surprise that many "how to" illustrations in user manuals are examples made up by their authors. Examples like these should accurately represent reality but they're not meant to be literally correct.

Who and What decides whether a literary work is creative?

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference works (dictionaries, encyclopedias, etc.) | Technical works (biological reports, engineering reports, etc.) |

| The impersonal and objective essay | High school chemistry or physics lab reports |

| Informational newspaper articles | Trip reports |

| Certain kinds of television news | Annual corporate reports |

| Certain kinds of nonfictional books (histories, geographies, catalogs, text books, etc.) | Scholarly research papers in academic subjects such as history and biography |

| Treatises | University syllabuses |

| PhD and Masters theses | Corporate policies and procedures manuals |

| Term papers | User manuals |

| Dissertations | Journals |

| The conjectural or personal essay | Course outlines |

Each of these writing styles is actually a class or group of writing styles. For example, the majority of different annual reports adhere to the same overall language characteristics for annual report writing styles, but one corporation may define a specific writing style for its annual report that differs in details from the style of another corporation.

In many cases, not all, the names for many of these expository prose writing styles are also the names for the literary forms that use them. For example, a dictionary is a book containing a selection of the words of a language, usually arranged alphabetically, giving information about their meanings, pronunciations, etymologies, inflected forms, etc.; they are expressed in either the same or another language. The majority of dictionaries use the same or a similar literary format and the same or a similar expository writing style. Consequently, these two aspects of dictionaries—writing style and literary format—have come to be identified with one another. So, most often when you pick up a Webster's dictionary you're not surprised if you see an expositional writing style which is almost the same as the one you see when you pick up a Random House dictionary.

Further complicating the expository name calling problem is the fact that two organizations may employ different literary formats or expository writing styles for an expository document they call by the same name. For example, a computer thesaurus is radically different from a paper-bound thesaurus such as The International Roget's Thesaurus.

Not only are the names of many expository writing styles the same as their literary forms, many expository literary forms and their writing styles are virtually identical with each other, even though they're called by different names. For example, a dissertation, treatise, and a thesis are essentially the same kind of exposition; they're different designations for the same thing. One source (a dictionary) defines them as:

Some sources might employ these terms interchangeably, as though they all designate the same kind of document; others might not, depending on the situation.

That's literary terminology ambiguousness for you!

If you're new to exposition, all this may seem a bit confusing at first, but at base it's really a very simple kind of writing. What's vital to remember concerning exposition—what all the expositional forms and writing styles have in common—is that they are all nonfictional.

Authors who write expositions often adopt a particular set of grammatical and literary guidelines, especially when they have strong reasons to objectify the material they write, to be impersonal. and to suspend emotional involvement. In order to appear more neutral and objective, they strive to remain anonymous.

For example, reference works like dictionaries and encyclopedias normally restrict names of linguists who compile their contents to a cover or title page; they often omit them completely. Corporate policies and procedures manuals and annual reports seldom identify their writing staff because they want to impress readers with a corporate image that appears larger than the individuals who work for it. This anonymity also helps insulate writers from possible public or third-party criticism.

Here are the grammatical and literary guidelines that help expository authors write in a neutral manner:

Most annual corporate reports, scholarly research papers on academic subjects, and user manuals possess these literary characteristics, to name a few.

An essay is a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.

It's

a kind of expository prose writing because its primary purpose is to expose

information and facts. However, it differs from other kinds of expository

prose writing in that its purpose also includes analyzing, speculating

about, and interpreting the information and facts it presents.

It's

a kind of expository prose writing because its primary purpose is to expose

information and facts. However, it differs from other kinds of expository

prose writing in that its purpose also includes analyzing, speculating

about, and interpreting the information and facts it presents.

Because of this more extensive purpose, the essay is a special variety of expository prose writing. It comes in two forms: The Muse Of Language Arts refers to these forms as: 1) the impersonal and objective essay, and 2) the conjectural or personal essay.

Most essays are one or the other of these two kinds of essay; some combine elements from each of them.

The impersonal and objective essay

Impersonal and objective essays display most of the literary characteristics of other kinds of expository narrative prose writing except that: 1) they follow a free-form prose literary structure that's at the discretion of the author, and 2) they objectively and impersonally explore, explain, analyze, speculate about, and interpret; they introduce conjectures and opinions; and they draw conclusions about relevant subjects, people, events, ideas, issues, etc.

These kinds of essays are free-form in the sense that authors are free to adopt any prose writing style they believe to be consistent with their purpose and appropriate for their audience, their publishing medium, or occasional circumstances. Usually that writing style is simple narrative prose that adheres to the grammar and literary characteristics of expository prose noted above. But authors are free to modify these characteristics if they see fit.

Impersonal and objective essays are a type literature that The Muse Of Literature spells with a lower case "l," as in literature; they do not belong to the type of literature that The Muse spells with a capital "L," as in Literature. Because authors of these kinds of essays normally seek to remain anonymous, personal and objective essays are normally penned in the third person.

Because it's unemotional and impersonal, this kind of essay is not writing in which expression and form, in connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic or essential features. It's literature spelled with a lowercase "l."

- Unfamiliar with lower case "l" literature and capital "L" Literature? Visit The Muse Of Literature's page titled "Literature" versus "literature" to find out what they are: tap or click here.

the conjectural or personal essay

Not all essays are completely impersonal, objective, and cool; some are very conjectural and very personal. For these reasons, The Muse calls essays like these conjectural or personal essays.

Impersonal and objective essays and conjectural or personal essays both follow a free-form prose literary structure that's at the discretion of the author. Because personally-felt reflections or causes are involved, these kinds of essays are normally penned in the first person.

However, unlike impersonal and objective essays, conjectural or personal essays are anything but objective and impersonal. Their primary purpose is to subjectively explore, explain, analyze, speculate about, and interpret; they introduce subjective conjectures and opinions; and they draw subjective, sometimes emotional conclusions about relevant subjects, people, events, ideas, issues, etc.

Authors choose to write these types of essays for a variety of reasons. Their purpose might be to:

Claim or publicize credit for something they've accomplished Convince or arouse readers to take action Prove a thesis Declare a personal victory Win an argument Make a point Speculate about a proposition or theory Achieve some a controversial, problematical, or personal objective Interpret or analyze something Convey anger or other emotions Convince readers to believe in, reject, or accept of an idea Publicly express gratitude, admiration, or disgust Win readers over to a cause Explain a heartfelt idea

Expositions like these usually belong to the type literature that The Muse Of Literature spells with a capital "L"—Literature. Expositions like these tend NOT to belong to the type of literature that The Muse spells with a lowercase "l"—literature.

Because it's emotional and personal, this kind of essay is writing in which expression and form, in connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic or essential features. It's Literature It's literature spelled with a capital "L."

As already noted many readers and writers accept the notion that nonfiction writing is uncreative just because it's not fictional. True, not all nonfiction writing is creative; much of it is even dull, drab, or commercial. But there's nothing that prevents nonfiction writers from exercising their imaginations and skills, from writing creatively, if they choose to do so. All they have to do is assume the right mind set and sit up straight, to remain fresh, bright, and alive.

Take expository writing for an example. Expository writing is writing or speech primarily intended to convey information or to explain; it's a detailed statement or explanation; it's an explanatory treatise:

No kind of nonfictional writing is more nonfictional than expository prose. Yet, if you examine The Muse's description of the nature of creative writing that you'll find near the top of this page and compare it with the varieties of expository prose outlined in the preceding sections, you'll probably conclude that expository prose writing can be very creative.

After all, nothing can grab your attention like the news of the day when war is immanent and bombs are dropping, or when a government official has been assassinated. A high school or college valedictorian speech will wake you up after a long hard night of partying, especially if it's delivered skillfully by someone you admire. And announcing record breaking profits to your investors is likely to wake them out of a sound sleep, especially if it's clear to the audience why it's getting rich.

It's relatively easy for an author to think up original things to say about situations like these. It's harder but still possible to conceive of interesting and new ways to express facts about dry nonfiction subjects, if only you invest the time and energy.

Conjectural or personal essays are another example of nonfictional writing that can be among some of the most creative writing ever penned. They take many forms and styles, including:

An essay is a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.

Essays are among the greatest compositions ever penned. Some of their authors are among our greatest writers. They include Francis bacon, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert Burns, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Baudelaire, Thomas De Quincy, Alexander Dumas, Johann Goethe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Heinrich Heine, John Keats, Edgar Allen Poe, Alexander Pushkin, Sir Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Germaine De Staël, Stendhal, and William Wordsworth. The list goes on and on.

Most essays are an expression of their authors' heartfelt opinions and ideas about subjects such as religion, politics, equal rights, torture, health, social issues, hunger, and other serious, profound, and important subjects. If you write an essay about something you believe in and feel deeply, it's easy to set down your thoughts in a way that projects your emotions to your readers, even while you bring forth facts and data to substantiate your case.

There's also room for creativity for writers who produce impersonal and objective essays, as well as for writers of expository writing generally. There are imaginative ways to skirt boredom despite the severe grammatical and literary restrictions these literary forms impose.

Nonfiction doesn't stop with expository prose and essays. General nonfiction is the

branch of literature comprising works of narrative prose dealing with or offering opinions or conjectures upon facts and reality. This branch includes biography and history, as well as other literary fields. What could pose more creative and challenging opportunities for creativity than writing a biography about yourself or about someone else who has lived an exciting or deplorable life, or about an important period in history? There's plenty of room for creativity when writing about people and events like these.As just noted, some pieces of nonfictional writing are creatively written, others not. By the same token, some pieces of fictional writing may not be creative because they are dull, boring, and unimaginative.

One of the most important kinds of creative writing is the kind of writing that goes on whenever a competent novelist pens a book. Understanding how and why novel writing is a creative art form is a great way to explore the nature of creative writing of all kinds.

|

| Jane Austen, the first true great modern novelist |

The modern novel is defined as a fictitious prose narrative of considerable length and complexity portraying characters and usually presenting a sequential organization of action and scenes. Its characters, events, actions, scenes, and situations are usually all created up by its author (i.e., they're fictional); but other elements such as places and times may be actual or may be invented depending on the author's preferences.

Even fictional elements such as places, actions, and situations may be based on actual characters, events, actions, and situations, but if so the details of their description, conversation, etc. are the result of the author's imagination. They're fictional because they're not historically and factually displayed.

The practice of telling stories like these actually began in antiquity, thousands of years ago, when people used speech to tell stories because writing didn't exist. Today's novels are distinctly different written works that only distantly resemble their forefathers.

Written works that tell fictional stories—literary works that people once called novels or gave other names to—preceded today's modern novels over a time span lasting many centuries, or even millennia. During this evolution individual authors randomly invented and perfected their own writing styles. Theirs was mostly a trial and error process.

The modern novel—that is, the kind of novel being written now—represents the culmination of this long process; it's a comparatively new development, one far more recent than the first kinds of novels that were written. The literary form of today's modern novels represents the summit of hundreds and even thousands of years of creative experimentation that preceded it.

As a result of all this trial and error experimentation with prose narrative stories, today's modern novels are literature that is technically and aesthetically far superior and much more sophisticated vehicles for recounting prose narrative stories. They're more aesthetic, effective, artistic, and creative literary works differing from their predecessors in major technical and linguistic ways.

Hundreds of thousands (even millions) of written fictional works have been created by authors over the millennia, only a small fraction of which are stored in libraries or on computers. Despite this vast production, the original sources for fictional writing are unknown or can only be surmised.

Much that happened long ago to bring about this first ancient advancement in telling stories is unknown. We can't be sure precisely how literary story-telling came about; we can only presume that somehow the human brain changed. It changed both in the way mankind understood stories and in the way it told them.

However, where the modern novel is concerned, history does permit us to pick up threads of the story of how the novel was invented because it's a story that began much later, after printing began, and these records still exist. From these records, it's easy to conclude that the modern novel and it's immediate predecessors were invented by a collection of writers working mostly independently of one another in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Not only did these writers invent the modern novel, which is a fictional literary structure; they also devised many of the various literary styles and techniques it employs. Thus, this group of writers gave birth both to the novel and to the way to write it.

Why did they go through this effort? They invented both the modern novel's structure and its writing styles and techniques because they needed both a new literary form and a new writing style in order to achieve the literary results they wanted.

A great number of other kinds of fictional and nonfictional prose narrative works have appeared since the creation of the modern novel in England; they have adopted literary forms and writing styles that are similar to those of the modern novel in great numbers. Thus, the modern novel has played a key role in defining the entire field of modern fictional and nonfictional writing, not just writing for the novel form alone.

This deduction is confirmed by tracing the evolutionary development of fictional and nonfictional narrative writing which occurred in England before, during, and after the modern novel's nascency. Whether in England, France, or other Western countries, no other kind of new narrative prose fiction or nonfiction writing that appeared on the scene so closely resembled those of the modern novel.

And further, after those original creative literary periods fell away into history, other new fictional literary forms, genres, and writing styles evolved from those used by the first modern novel writers. They evolved apace with each other and in parallel with each other throughout Europe, and eventually even in Asia.

Thus the modern novel has played a decisive role in deciding the nature of creative writing in the modern world, not only in fictional genres at large but in nonfictional genres as well. Today the modern novel is a pervasive medium; it's written, sold, bought, and read in vast quantities in almost every corner of the globe.

How do fictional and nonfictional literature compare with one another?

The traditional definition for nonfictional literature, the one favored by the preponderance of literati, book stores, publishers, and many readers, is that nonfiction is the branch of literature comprising works of narrative prose dealing with or offering opinions or conjectures upon facts and reality, including biography, history, and the essay.

The traditional definition for fictional literature, the one favored by the preponderance of literati, book stores, publishers, and many readers, is that fiction is the class of literature comprising works of imaginative narration, especially in prose form.

But these definitions come to us from literary purists. In reality, biography, history, conjectural or personal essays, and other kinds of literature usually consist of a mixture of both nonfiction and fiction.

Yes, nonfictional biography, history, conjectural or personal essays, and other nonfictional works usually are based on objective facts and contain lots of nonfictional writing.

But consider English historian Edward Gibbon's six-volume book first published in 1776, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was intended by its author to be a definitive nonfictional history that traces the trajectory of Western civilization, including the Islamic and Mongolian conquests, from the height of the Roman Empire to the fall of Byzantium.

At first glance one might expect a history like this to be totally and completely nonfictional, but it isn't. It's filled with Gibbon's personal reflections that he writes subjectively in the first person; it contains controversial and error-filled chapters; and it's missing relevant facts and information, some of which Gibbon he manufactures from his own imagination, guesses at, speculates about, or virtually invents out of whole cloth.

Despite it's defects, all things considered this nonfictional history is a skillfully and cleverly written, highly creative literary work. It's the kind of writing The Muse refers to as literature with a capital "L."

Is this history book nonfiction or fiction? Is it highly creative or plebeian? Is it literature with a capital "L" or literature with a lowercase "l"?

You decide.

Yes, fiction is the class of literature comprising works of imaginative narration, especially in prose form.

But consider Irving Stone's fictional historical novel The Agony and the Ecstasy. Stone intended his book to be a biographical novel of the great Italian Renaissance painter Michelangelo Buonarroti, one that depicts the Italian history and culture in which the painter had been immersed. It explores the character's interaction between himself and his surroundings.

To make it authentic, Stone based his book on 495 letters of Michelangelo's personal correspondence, sculptures, paintings, and other historic materials, which he used to piece together a realistic picture of the painter's life. So accurate was Stone's fictional writing, the Italian government lauded him with several awards for his achievements in highlighting Italian history. Yet so imaginative and creative was his writing, his book remained on bestseller lists for weeks and months.

At first glance one might expect an historic novel like this one to be be highly inventive, and it is; it was filled with made-up dialogue, fabricated situations, subplots that didn't really happen, concocted characters, and other inventions, some based loosely on factual information he'd gathered, others totally his own.

Many of Stone's readership felt that his book was essentially a lie that had little to do with the real Michelangelo or his historical surroundings; they believed that the book was rife with intellectual shortfalls, errors, and misunderstandings, and they resented their belief that the book misinformed and cheated them. Other readers felt that the book was well worth reading because it revealed the spiritual essence of Michelangelo's life and career, his artistic significance, and his many contributions to their cultural inheritance, and did so in an entertaining and enjoyable manner. They were delighted to learn more about the painter's works, what they stood for, and what he had contributed to our culture. Never mind the inaccuracies; if there really were error or omissions, they were only details.

Is this history book in novel form fiction or nonfiction? Did Stone stretch the truth too much to be trusted? Or are the book's fabrications legitimate because they allowed him to get to the heart of what mattered? Given that it's skillfully and cleverly written, is it a highly creative literary work or merely a chest thumper? Is it the kind of writing The Muse refers to as literature with a capital "L" or is it an aesthetic, clumsy, insulting bust?

You decide.

Conclusion

- Whatever you decide about these two books, the notion that there's a clear line between fictional and nonfictional writing is a itself a fiction. Although there are sharp differences between the two kinds of writing, in reality the line between them is a blurry one. Fiction and nonfiction are more similar means of communication than many readers and writers realize. Writers often produce a mixture of both kinds of writing.

- Conventional wisdom asserts that fiction and nonfiction are opposites. That's not the case; actually they're consistent with one another. It's more accurate to say that fiction and nonfiction are complementary and supplementary to one another. This truism applies both to literature with a capital "L" and literature with a lowercase "l."

- Both fiction and nonfiction offer authors significant opportunities for creativity. The different writing techniques they choose to use for a specific work at hand depend on its literary format, purpose, audience, and circumstantial factors. These techniques are universal; they're available to every writer who possesses the skill, knowhow, and creativity to apply them.

As mentioned above, people often misuse literary terms when they talk about subjects such as creative writing. The words fiction and nonfiction are two of the most abused terms. Which of these two words ar the right ones to use to describe a given piece of literature?

Conventional usage holds that nonfiction is the branch of literature comprising works of narrative prose dealing with or offering opinions or conjectures upon facts and reality; it includes biography (of the non-conjectural kind), history, and the essay.

By contrast, fiction is the class of literature comprising works of imaginative narration, especially in prose form, including narrative prose works such as a novels and short stories, as well as in poetry and drama. Some written works composed with these literary forms may be based on fact, but if so they are primarily the imaginative creations of their authors and hence they are at base fictional.

For these reasons, most literati consider fiction and nonfiction to be opposites, and they distinguish nonfiction from poetry and drama. When speaking of bodies of literature as a whole, they regard fiction to be writing that is creative and nonfiction to be writing that is not creative. This conventional wisdom is accepted by the public at large.

This usage is quite appropriate when made unambiguous by its context. The Muse Of Language Arts and The Muse of Literature recommend that you feel free to employ these terms in this conventional manner whenever you see fit.

However, The Muse recommends that creative writing terminology be employed more accurately when the genuine differences between fiction and nonfiction are under discussion. Fictional and nonfictional writing are not actually contrary or opposing forms of writing, and this distinction should be observed.

Yes, reality is the direct opposite of unreality where objective facts about the natural world are under consideration; but contrary to literary convention, fiction is not the direct opposite of nonfiction where writing is concerned. In actuality, fiction and nonfiction are alike in the sense that both deal real objects and events that behave in realistic ways.

Notice that a given nonfictional work may contain fictional passages or references to fictional entities; and a given fictional work may contain nonfictional information. A given fictional work often will expound, set forth, explain, or present facts and other nonfictional information; it may contain characters, events, settings, actions that describe real people or historic events. Thus the distinction between fictional and nonfictional literature is a blurred one.

Then what's the operative, effective, most basic distinction between fiction and nonfiction, the one that makes the most difference? It's simply this: authors treat facts differently when they write fiction. Authors who write fiction blend and bend facts to suit their imaginations, whereas authors who write nonfiction adhere to facts as closely as possible.

Fiction and nonfiction are alike in two other key ways: Copious quantities of both fictional and nonfictional writing are subjected to abuse by authors who write dully; and relatively limited quantities of both fiction and nonfiction are treated with respect by authors who write with originality of thought and expression.

As a consequence, the terms creative writing and uncreative writing bear an apples-and-oranges relationship to each other, as well as to the terms fiction and nonfiction. Uncreative writing is not a synonym for nonfictional writing, nor is it an antonym for fictional writing.

Because of this apples-oranges relationship, The Muse Of Language Arts prefers to refer to dull, cheerless and inspired fictional writing as uncreative writing; and The Muse prefers to refer to to dull, cheerless and uninspired nonfictional writing by the same term, as uncreative writing.

Consequently, there's nothing inherently wrong with describing a fictional (so-called creative) work such as a novel, short story, or a detective story as uncreative writing, so long as you genuinely believe that it's unimaginative and unoriginal in the true sense of the term not creative. Many fictional works are examples of uncreative writing in this sense of the term.

Nor is there a problem with describing a nonfictional work as creative, if you genuinely believe that it demonstrates intellectual creativity.

A modern novel is a fictitious prose narrative (i.e., a concocted story or imaginary account) of considerable length and complexity portraying characters and usually presenting a sequential organization of actions and scenes.

The current body of modern novels is an amazing collection that includes brilliant authors and masterpieces, works exhibiting striking beauty and significance that sparkle with artistic excellence. Compared with other kinds of important literary works that tell stories—and there are many of them—modern novels account for an amazing number of the greatest books ever written.

The modern novel literary form has just experienced its two hundredth birthday. Two hundred years may seem like too long a time to call the modern novel modern, but modern is a relative term. Considering how long mankind has been telling stories that are not novels, even at two centuries the modern novel is a relatively recent development.

What, then, are the literary and linguistic traits that make modern novels truly different from all these other ways to tell stories, and special? What are their technical specs: their literary forms, genres, language characteristics, and other properties? What is it about modern novels that makes them especially effective and meritorious? When, where, how, why, and by whom were they originally conceived?

|

|

Search this web site with Electricka's Search Tool:

tap or click here

Electricka's Theme Products

Shop At Cafe Press

This web site and

its contents are copyrighted by

Decision Consulting Incorporated (DCI).

All rights reserved.

Contact Us

Print This Page

Add

This Page To Your Favorites (type <Ctrl> D)

You may reproduce this page for your personal

use or for non-commercial distribution. All copies must include this

copyright statement.

—Additional

copyright and trademark notices—

| Exploring the Arts Foundation |

|

| Today's Special Feature |

| Search Now |

| To Do |

| To Do More |

| See Also |

| Our Blogs |

| Our Forums | ||

|

|

Resource Shelf |

| ETAF-Amazon |

|

|